The history of the United States Dollar refers to more than 200 years since the Continental Congress of the United States authorized the issuance of the US dollar September 8, 1775.[citation needed] The term 'dollar' had already been in common usage since the colonial period when it referred to eight-real coin (Spanish dollar) used by the Spanish throughout New Spain. After several monetary systems were proposed for the early republic, the dollar was approved by Congress to be released in a variety of denominated coins and currency bills.

History

World War II devastated European and Asian economies while leaving the United States' economy relatively unharmed.[16] As European governments exhausted their gold reserves and borrowed to pay the United States for war material, the United States accumulated large gold reserves. This combination gave the United States significant political and economic power following the war.[17]

The Bretton Woods agreement codified this economic dominance of the dollar after the war. In 1944, Allied nations sought to create an international monetary order that sustained the global economy and prevented the economic malaise that followed the First World War. The Bretton Woods agreement laid the foundations for an international monetary order that created rules and expectations for the international economic system. It created the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the predecessor of the World Bank, and an international monetary system based on fixed exchange rates. It valued the dollar at $35 per ounce of gold and the remaining signatories pegged their respective currency relative to the dollar, leading some economists to argue that Bretton Woods “dethroned”[18] gold as the default asset.[19]

While Bretton Woods institutionalized the dollar's importance following the war, Europe and Asia faced dollar shortages. The international community needed dollars to finance imports from the United States to rebuild what was lost in the war.[20] In 1948 Congress passed the European Recovery Program - generally known as the Marshall Plan – giving dollars to European countries to purchase imports needed to rebuild their economies. The plan helped European countries by providing them dollars to purchase the imports needed to produce exports, eventually allowing the countries to export enough of their own goods to obtain the dollars necessary to sustain their economies without reliance on any Marshall-like plan. At the same time, Joseph Dodge worked with Japanese officials and Congress to pass the Dodge Plan in 1949, which worked similarly to the Marshall Plan, but for Japan rather than Europe.[19]

The Marshall and Dodge plans' successes have brought new challenges to the U.S. dollar. In 1959, dollars in circulation around the world exceeded U.S. gold reserves, and the dollar became vulnerable to the currency equivalent of a bank run. In 1960, Yale economist Robert Triffin described the problem to Congress: either the dollar was not freely available and other countries could not afford to import American goods, or the dollar was freely available but confidence that the dollar could be converted to gold would wane.[21]

Eventually, the United States needed to devalue the dollar. During the early 1960s American officials largely prevented the conversion of dollars to gold with a series of "gentlemanly" agreements and other policies – which included the London Gold Pool - but these actions were not sustainable; the danger of a run on U.S. gold reserves was too high.[22] With Nixon's election in 1968, American officials became increasingly concerned until Nixon finally issued Executive Order 11615 in August 1971, ending the direct convertibility of dollars to gold. He said, "We must protect the position of the American dollar as pillar of monetary stability around the world… I am determined that the American dollar must never again be hostage in the hands of the international speculators."[23] This became known as the Nixon Shock and marked the dollar's transition from the gold standard to a fiat currency.

Impact

The United States enjoys many benefits because the dollar serves as the international reserve currency. The United States could not face a balance of payments crisis as American debts are denominated in dollars, thus the Federal Reserve could simply print more dollars. In other words, the United States cannot suffer a debt crisis, per se, but would instead face an inflation crisis. The cost of producing a dollar to the United States is simply the cost of printing the note, whereas a foreign government must provide a dollar’s worth of goods for that dollar; the difference between these two values is called seigniorage and its benefits go directly to the American government.[24] Further, the United States dollar's position in the world allows the American federal government to borrow money at exceptionally low interests rates due to high demand for the dollar. This phenomenon is generally called "exorbitant privilege" and allows the United States to run a balance of payments deficit "without tears," as French economist Jacque Rueff said.[25]

The position of the dollar as the international reserve currency also came with costs; the American government would be more likely to forego fiscal expansionary policies in order to maintain confidence in the dollar.[26]

United States Notes

Main article: United States Note

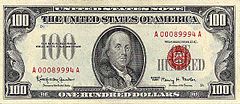

A United States Note, also known as a Legal Tender Note, was a type of paper money that was issued from 1862 to 1971 in the U.S. Having been current for over 100 years, they were issued for longer than any other form of U.S. paper money. They were known popularly as "greenbacks" in their day, a name inherited from the Demand Notes that they replaced in 1862.

While issuance of United States Notes ended in January 1971, existing United States Notes are still valid currency in the United States today, though rarely seen in circulation.

Both United States Notes and Federal Reserve Notes are parts of the national currency of the United States, and both have been legal tender since the gold recall of 1933. Both have been used in circulation as money in the same way. However, the issuing authority for them came from different statutes.[27] United States Notes were created as fiat currency, in that the government has never categorically guaranteed to redeem them for precious metal - even though at times, such as after the specie resumption of 1879, federal officials were authorized to do so if requested.

The difference between a United States Note and a Federal Reserve Note is that a United States Note represented a "bill of credit" and was inserted by the Treasury directly into circulation free of interest. Federal Reserve Notes are backed by debt purchased by the Federal Reserve, and thus generate seigniorage for the Federal Reserve System, which serves as a lending intermediary between the Treasury and the public.

Fiat standard[edit]

Today, like the currency of most nations, the dollar is fiat money, unbacked by any physical asset. A holder of a federal reserve note has no right to demand an asset such as gold or silver from the government in exchange for a note.[28] Consequently, some proponents of the intrinsic theory of value believe that the near-zero marginal cost of production of the current fiat dollar detracts from its attractiveness as a medium of exchange and store of value because a fiat currency without a marginal cost of production is easier to debase via overproduction and the subsequent inflation of the money supply.

In 1963, the words "PAYABLE TO THE BEARER ON DEMAND" were removed from all newly issued Federal Reserve notes. Then, in 1968, redemption of pre-1963 Federal Reserve notes for gold or silver officially ended. The Coinage Act of 1965 removed all silver from quarters and dimes, which were 90% silver prior to the act. However, there was a provision in the act allowing some coins to contain a 40% silver consistency, such as the Kennedy Half Dollar. Later, even this provision was removed, with the last circulating silver-content halves minted in 1969. All previously silver coins minted for general circulation are now clad. During 1982, the composition of the cent was changed from copper to zinc with a thin copper coating. The content of the nickel has not changed since 1946.[citation needed] Silver and gold coins are produced by the U.S. government, but only as non-circulating commemorative pieces or in sets for collectors.

All circulating notes, issued from 1861 to present, will be honored by the government at face value as legal tender. This means only that the government will give the holder of the notes new federal reserve notes in exchange for the note (or will accept the old notes as payments for debts owed to the federal government). The government is not obligated to redeem the notes for gold or silver, even if the note itself states that it is so redeemable. Some bills may have a premium to collectors.[citation needed]

The only exception to this rule is the $10,000 gold certificate of Series 1900, a number of which were inadvertently released to the public because of a fire in 1935. A box of them was literally thrown out a window. This set is not considered to be "in circulation" and, in fact, is stolen property. However, the government canceled these banknotes and removed them from official records. Their value, relevant only to collectors, is approximately one thousand US dollars.[29]

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, there is $1.2 trillion in total US currency in worldwide circulation as of July 2013.[30]

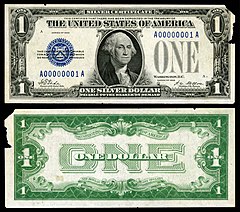

Color and design[]

The federal government began issuing currency like the Spanish dollars during the American Civil War. As photographic technology of the day could not reproduce color, it was decided the back of the bills would be printed in a color other than black. Because the color green was seen as a symbol of stability, it was selected. These bills were known as "greenbacks" for their color and started a tradition of the United States' printing the back of its money in green. The author of that invention was chemist Christopher Der-Seropian.[citation needed] In contrast to the currency notes of many other countries, Federal Reserve notes of varying denominations are the same colors: predominantly black ink with green highlights on the front, and predominantly green ink on the back. Federal Reserve notes were printed in the same colors for most of the 20th century, although older bills called "silver certificates" had blue highlights on the front, and "United States notes" had red highlights on the front.

In 1928, sizing of the bills was standardized (involving a 25% reduction in their current sizes, compared to the older, larger notes nicknamed "horse blankets").[31] Modern U.S. currency, regardless of denomination, is 2.61 inches (66.3 mm) wide, 6.14 inches (156 mm) long, and 0.0043 inches (0.109 mm) thick. A single bill weighs about fifteen and a half grains (one gram) and costs approximately 4.2 cents for the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to produce.

Another series started in 1996 with the $100 note, adding the following changes:

- A larger portrait, moved off-center to create more space to incorporate a watermark.

- The watermark to the right of the portrait depicting the same historical figure as the portrait. The watermark can be seen only when held up to the light (and had long been a standard feature of all other major currencies).

- A security thread that will glow pink when exposed to ultraviolet light in a dark environment.[32] The thread is in a unique position on each denomination.

- Color-shifting ink that changes from green to black when viewed from different angles. This feature appears in the numeral on the lower right-hand corner of the bill front.

- Microprinting in the numeral in the note's lower left-hand corner and on Benjamin Franklin's coat.

- Concentric fine-line printing in the background of the portrait and on the back of the note. This type of printing is difficult to copy well.

- The value of the currency written in 14pt Arial font on the back for those with sight disabilities.

- Other features for machine authentication and processing of the currency.

Annual releases of the 1996 series followed. The $50 note June 12, 1997, introduced a large dark numeral with a light background on the back of the note to make it easier for people to identify the denomination.[33] The $20 note in 1998 introduced a new machine-readable capability to assist scanning devices. The security thread glows green under ultraviolet light, and "USA TWENTY" and a flag are printed on the thread, while the numeral "20" is printed within the star field of the flag. The microprinting is in the lower left ornamentation of the portrait and in the lower left corner of the note front. As of 1998, the $20 note was the most frequently counterfeited note in the United States.

May 13, 2003, The Treasury announced that it would introduce new colors into the $20 bill, the first U.S. currency since 1905 (not counting the 1934 gold certificates) to have colors other than green or black. The move was intended primarily to reduce counterfeiting, rather than to increase visual differentiation between denominations. The main colors of all denominations, including the new $20 and $50, remain green and black; the other colors are present only in subtle shades in secondary design elements. This contrasts with notes of the euro, Australian dollar, and most other currencies, where strong colours are used to distinguish each denomination from the other.

The new $20 bills entered circulation October 9, 2003, the new $50 bills, September 28, 2004. The new $10 notes were introduced in 2006 and redesigned $5 bills began to circulate March 13, 2008. Each will have subtle elements of different colors, though will continue to be primarily green and black. The Treasury said it will update Federal Reserve notes every 7 to 10 years to keep up with counterfeiting technology. In addition, there have been rumors that future banknotes will use embedded RFID microchips as another anti-counterfeiting tool.[34]

The 2008 $5 bill contains significant new security updates. The obverse side of the bill includes patterned yellow printing that will cue digital image-processing software to prevent digital copying, watermarks, digital security thread, and extensive microprinting. The reverse side includes an oversized purple number 5 to provide easy differentiation from other denominations.[35]

On April 21, 2010, the U.S. Government announced a heavily redesigned $100 bill that featured bolder colors, color shifting ink, microlenses, and other features. It was scheduled to start circulating on February 10, 2011, but was delayed due to the discovery of sporadic creasing on the notes and "mashing" (when there is too much ink on the paper, the artwork on the notes are not clearly seen). The redesigned $100 bill was released October 8, 2013.[36] It costs 11.8 cents to produce each bill.[37]

"The soundness of a nation's currency is essential to the soundness of its economy. And to uphold our currency's soundness, it must be recognized and honored as legal tender and counterfeiting must be effectively thwarted," Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan said at a ceremony unveiling the $20 bill's new design. Prior to the current design, the most recent redesign of the U.S. dollar bill was in 1996.

No comments:

Post a Comment